If you could change a single letter in your DNA, would anything actually happen?

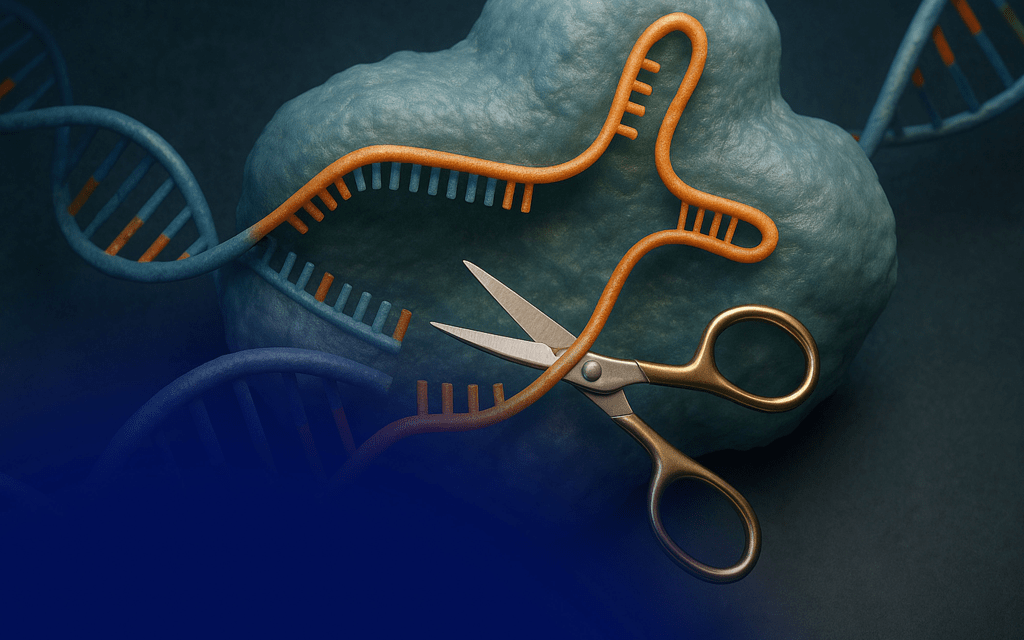

That question sounds like science fiction, but modern biology has turned it into something astonishingly real. The tool behind this revolution is CRISPR: a molecular “find-and-edit” system borrowed from bacteria. In nature, bacteria use CRISPR as a defense system against viruses. In the lab, scientists realized the same machinery can be guided to almost any gene we want. Give it an address, and it goes there.

That sounds dramatic, but here’s the wild part: this isn’t only happening in giant government labs.

When I was 12, I did a CRISPR experiment at home.

Using an at-home educational kit from The ODIN, I edited a single gene in E. coli bacteria called rpsL. At one exact position in that gene, number 43, the normal bacteria have the amino acid lysine (K). With CRISPR, I changed that single amino acid to threonine (T). Scientists write that change as K43T.

One letter in the DNA changed. One amino acid swapped.

But the consequence was visible to the naked eye.

Normally, harmless E. coli can’t grow on plates that contain the antibiotic streptomycin. After the mutation, the bacteria could grow. The K43T change altered the ribosomal protein targeted by the antibiotic, so the drug couldn’t stop the bacteria anymore. Same species, same cells, just one tiny change that made a huge difference in survival.

Seeing colonies appear where nothing should have grown is a moment you don’t forget.

And that’s really the magic of genetics: small changes can matter.

CRISPR isn’t about instantly “designing” humans or making science-fiction monsters. It’s about precision. In the past, changing DNA was like throwing paint at a wall and hoping a droplet hit the right spot. CRISPR is closer to using a pen. It allows scientists to study diseases, build better crops, and understand how life works by changing one variable at a time.

Of course, with power comes responsibility. Real CRISPR work requires thinking about safety, ethics, and rules, what should be edited, not just what can be edited. Many applications belong in controlled labs and under regulation. But what surprised me was how accessible the learning side is becoming.

Educational biotech kits now exist so students can explore genetics safely, legally, and hands-on. The ODIN kit I used didn’t create anything dangerous or exotic. What it did create was curiosity: the feeling of: I can understand this. I can do science.

If you’re interested in genetics, I genuinely recommend exploring kits like that. Not because they turn you into a “gene editor overnight,” but because they transform biology from words in a textbook into something alive and testable. Watching living cells respond to a single genetic change teaches you more than five chapters of notes ever could.

CRISPR is not magic. It’s a tool.

The real magic is realizing that life is written in a code, that the code can change, and that we now have a way to read it, and sometimes even rewrite a letter.

And that journey can start earlier, and be more accessible, than most people think.